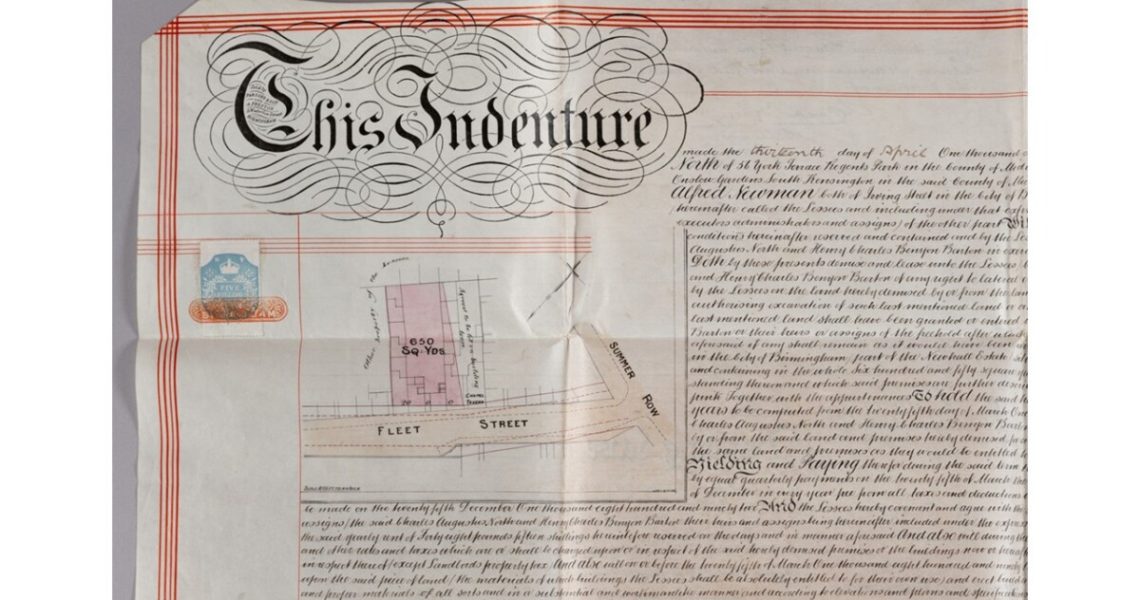

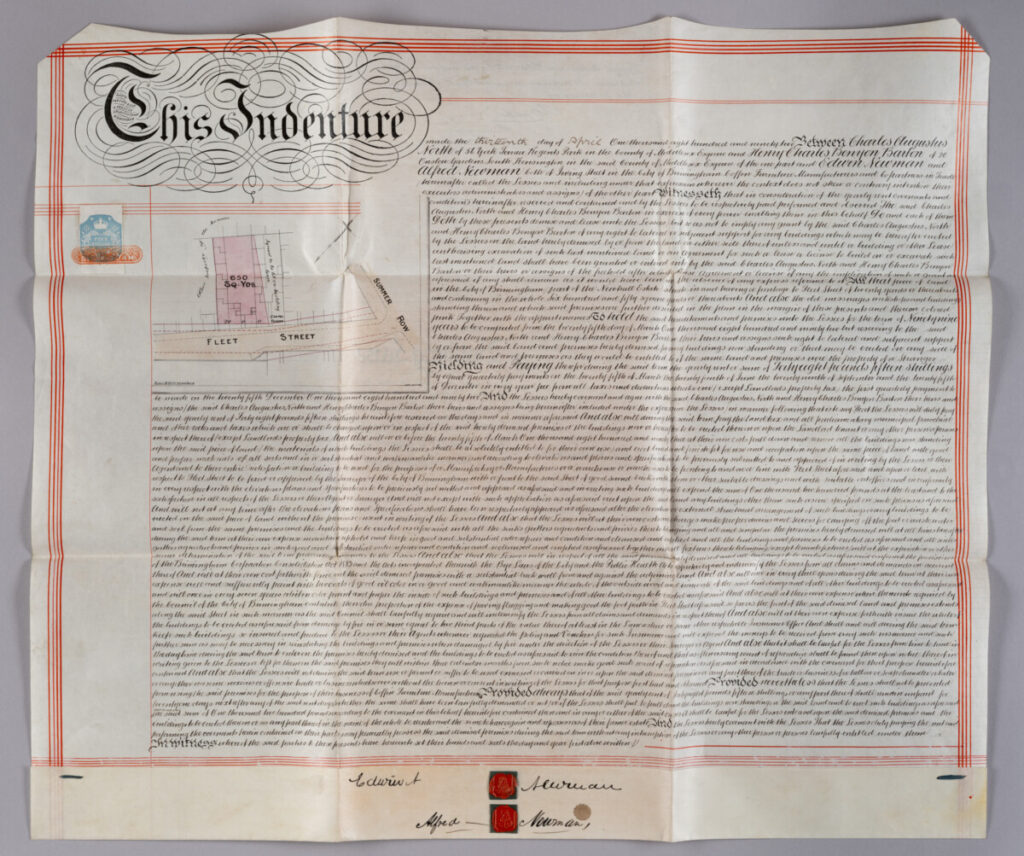

In April 1892, a lease was signed for a plot of land on Fleet Street in Birmingham. On the surface, it was a typical legal document: land, rent, and a list of conditions. But it also reflects the way the city was developing—expanding industry, formal agreements, and long-term plans between property owners and local tradesmen.

The lease was between Charles Augustus North and Henry Charles Benyon Barton, both based in London and Edwin and Alfred Newman, coffin furniture manufacturers from Birmingham. It covered a 99-year term, starting 25th March 1892 and ending 25th March 1991, with an annual rent of £48.15s.0d, paid quarterly.

The Newhall Estate

The land in question was part of the Newhall Estate, which had once surrounded New Hall, the historic home of the Colmore family. Over the 18th and 19th centuries, the estate was gradually broken up and developed as Birmingham grew into a major industrial centre. Streets like Fleet Street, once part of open estate grounds, became home to small factories, warehouses, and workshops typical of the era. This lease was one small piece of that wider transformation.

The Agreement

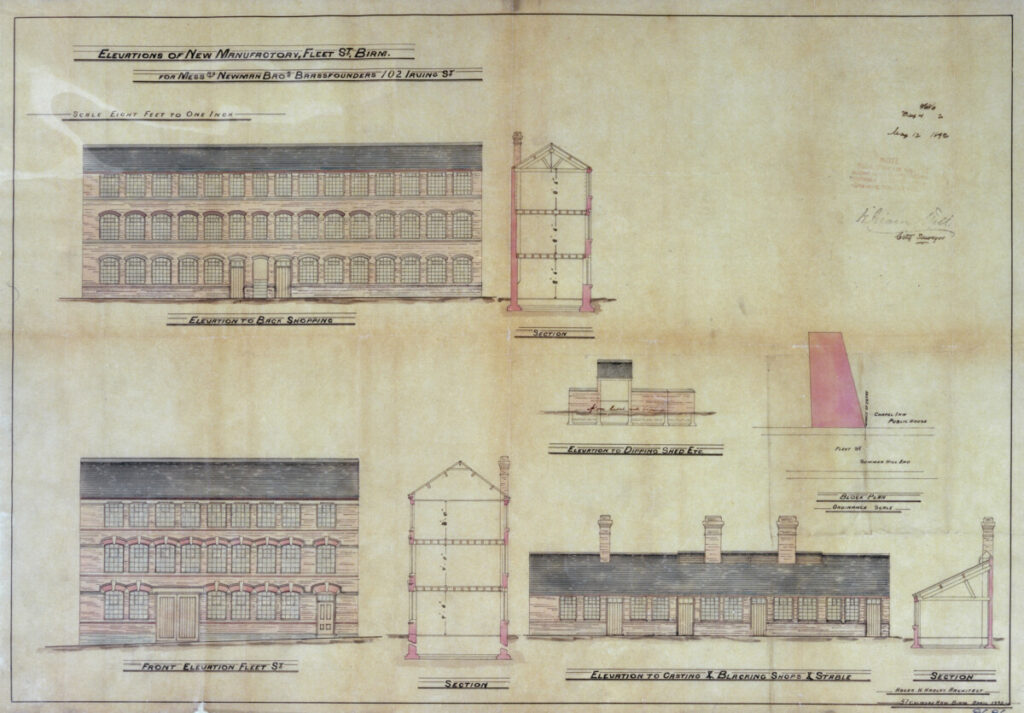

The Newmans leased a plot of around 650 square yards, including some old buildings they were required to demolish. In their place, they had to build a manufactory or warehouse and nothing less than £1,200 was to be spent, and everything had to meet the landlords’ approval.

They were responsible for all taxes (except the landlord’s property tax), proper drainage, fencing, regular maintenance, and complying with Birmingham’s building regulations. The building had to be fronted in brick with suitable stone or similar features, and it needed to align properly with Fleet Street. Plans and specifications had to be submitted and approved in writing before any work began.

Strict Terms

The lease made certain things very clear. The Newmans couldn’t change the structure without permission, use the site for any unpleasant trades (unless allowed), or fall behind on rent. If they didn’t meet the building or payment terms, the lessors, a legal term for landlords, could legally reclaim the property.

Insurance was also required. The building had to be insured for at least two-thirds of its value, and any damage had to be repaired using those funds. The lessors had the right to inspect the site during the term, and any required repairs had to be completed within three months of notice.

Looking Ahead

One can’t help but wonder if Edwin and Alfred Newman, standing on that plot in 1892, ever looked ahead 99 years and imagined what might still be there. Would the manufactory still be in the family? Would the building still be standing? Would the business still exist?

As it turns out, the building did survive, and the business endured far beyond its original lease. While it’s no longer in family hands and no longer a working manufactory, it lives on with a new identity. Today, in 2025, the site has been transformed into a museum, preserving the story of the Newman Brothers and their role in Birmingham’s industrial past. The document they signed wasn’t just a lease, it was the beginning of a story still being told.

Sarah Hayes, Museum & Trust Director