It’s been a year since we published our blog on the previously unknown Newman Brothers’ workforce we discovered as a result of the publication of the 1921 census.

We were happy with that, but it appears that there’s even more out there and it’s the census that keeps on giving. We’ve found additional names to add to the record and in some cases images too!

The Sewing Sisters

Let’s start with Katie and Ellen Cunningham. I’ve nicknamed them the ‘Sewing Sisters’ as they worked together in the Sewing Room. On the 1921 Census, they listed their occupation as ‘shroud makers’. Ellen was the eldest of the sisters at 22 and Katie was 18.

At this time, any work carried out by women was largely considered unskilled, regardless of how complex the task. This was no different for Ellen and Katie, who were highly-skilled seamstresses.

Copy of original census page from 1921 listing Katie and Ellen’s occupation and employer. © Find My Past.

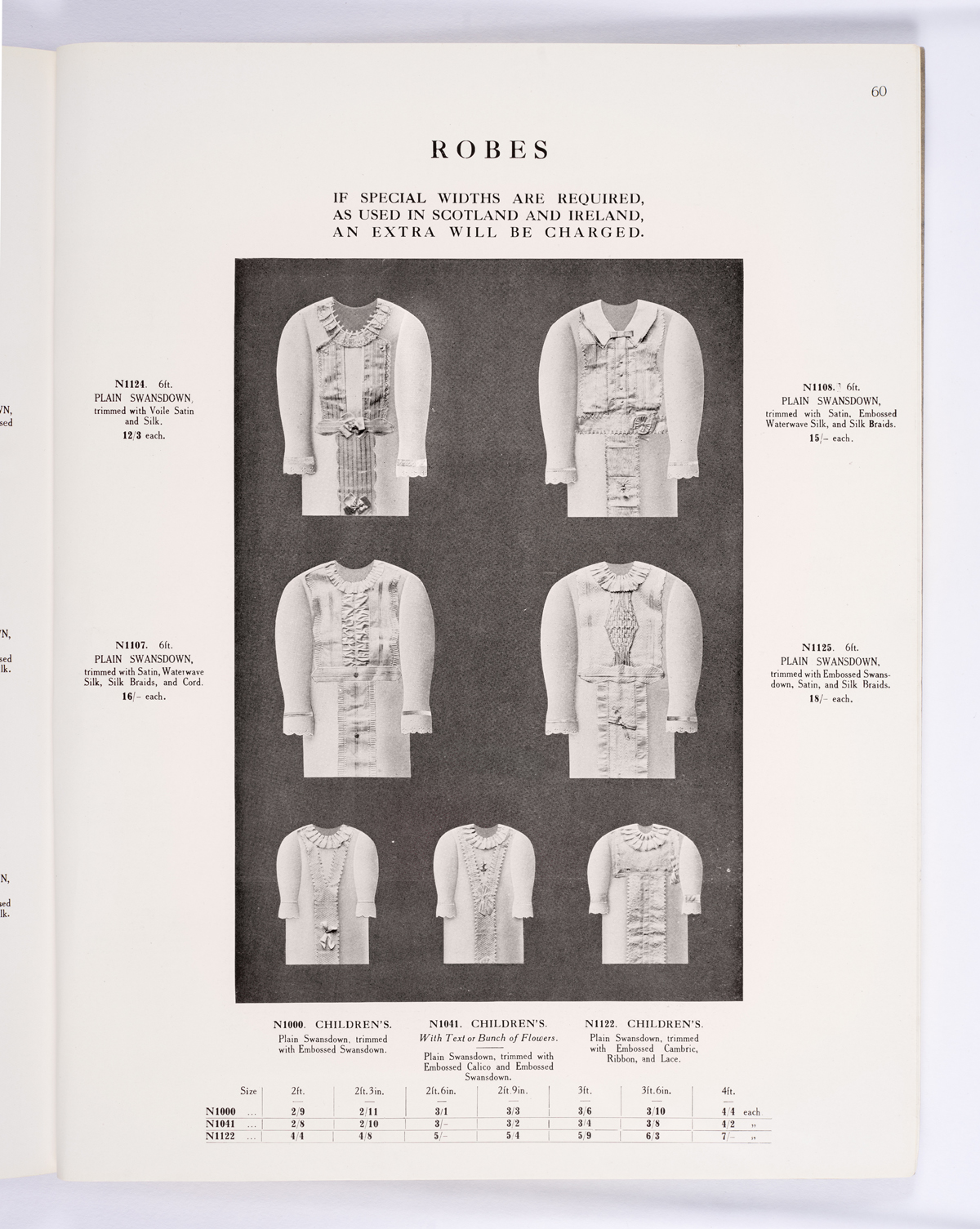

We’re fortunate enough to have a trade catalogue in our collection, dating from between 1915 to 1922, so we can take a look at the types of garments they would have made. The most expensive shroud listed in the catalogue was made from silk and satin and sold for 18 shillings.

Copy of page from Newman Brothers’ trade catalogue showing the types of garments the sisters would have made. © Coffin Works Museum.

Copy of page from Newman Brothers’ trade catalogue showing the types of garments the sisters would have made. © Coffin Works Museum.

To put that into context, the weekly wage for a female factory worker in 1920 was £1. 14s. 6d. That shroud was the equivalent of just over half a week’s wages for them.

The sisters were living in their family home in 1921, just 1.1 miles from Newman Brothers at 110 Icknield Port Square. It was about a 22-minute walk to work for them.

Copy of Passenger List from 1946, listing wives of Canadian soldiers leaving Britain for Saskatchewan © Images reproduced by courtesy of the National Archives, London England. Digitised by www.findmypast.com

Copy of Passenger List from 1946, listing wives of Canadian soldiers leaving Britain for Saskatchewan © Images reproduced by courtesy of the National Archives, London England. Digitised by www.findmypast.com

We haven’t managed to locate any photos of the sisters, but we do know that Ellen left on a passenger boat for Saskatchewan in August 1946, with her 10-year old son, John C. Hill. She was going to join her husband, Constantine Quinn, who was a Canadian Soldier. They were married in Birmingham, a year before at St Francis (most likely in Handsworth, where she was living). Constantine was Ellen’s second husband, as her first husband and father of her child, Reginald Charles Hill, died in 1941. From the passenger list, we can see that she listed her contact in Canada as ‘M. Quinn’, her husband’s father, who also lived in Saskatchewan.

Ellen died on 20th May 1977 at the age of 77 in Alberta, Canada. Her husband died at the age of 75 in 1990. Her sister, Katie, died in Walsall at the age of 80 in 1982.

‘Polisher, out of work’

We were fortunate enough to locate a photo of another worker though: Sarah Jane Bradbury, who later became Sarah Pimm. In the 1921 Census, she’s listed as a ‘Polisher, out of work’ and ‘Newman Brothers’ as her former employer.

Photo of the Newman Brothers’ workforce from 1912. Could Sarah feature in this photo? © Coffin Works Museum

Photo of the Newman Brothers’ workforce from 1912. Could Sarah feature in this photo? © Coffin Works Museum

In the 1911 census, Sarah is very much working and her occupation is recorded as ‘polisher’. Could she have been working at Newman Brothers then? Very possibly, and if so there’s a good chance she could feature in the only Newman Brothers’ staff photo from 1912. She would have been 28 at this point.

Sarah Jane in around 1918. © Molly Langbridge

Sarah Jane in around 1918. © Molly Langbridge

Sarah lived on Newhall Hill in 1911, which still exists today and is less than a 5-minute walk to the Newman Brothers’ Manufactory. She lived there with her husband, Henry Pimm, who she married in 1904. Later in 1921, her residence is recorded as Edward Street, just 0.3 miles from Newman Brothers. She died in 1950.

The street where Sarah lived in 1921. The image also shows the walking distance to Newman Brothers’ Manufactory, now home of the Coffin Works Museum. ©Google Maps

The street where Sarah lived in 1921. The image also shows the walking distance to Newman Brothers’ Manufactory, now home of the Coffin Works Museum. ©Google Maps

We’re hopeful that we will make more discoveries and as we find more information, we’ll keep on updating our records and sharing it in our blogs. Watch this space!

You can read our previous blog on the 1921 census by clicking here.

Special thanks to Suzanne Hayes, who continues to support our research efforts.

Written by Sarah Hayes, Museum Manager